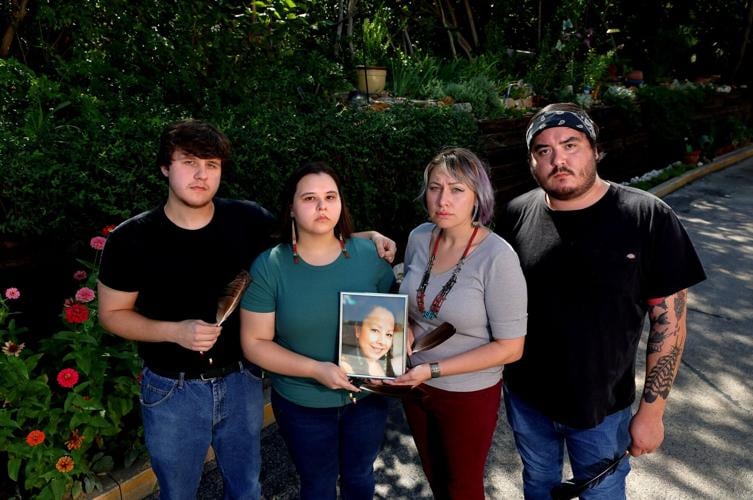

Cole Taylor, from left, Rose Taylor, Rachael Benns and Nick Kettler gather with a photo of their aunt Kathleen ŌĆ£KatŌĆØ Dunkus on Monday, Aug. 28, 2023. Dunkus died of heart issues at Mercy Hospital ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ in a locked unit where psychiatric patients are kept. The family members are holding feathers with beads that were handed out at her funeral to honor their Oglala Lakota Native American roots.

CREVE COEUR ŌĆö Kat Dunkus was doing better. She had moved in with her niece after completing an alcoholic treatment program two years ago. The program helped her learn better ways to cope with her schizophrenia and trauma.

ŌĆ£She was trying to find her way back to more stability. She was trying to find happiness for herself,ŌĆØ said her niece Rachael Benns, 31, of Creve Coeur. ŌĆ£She kept saying, ŌĆśIŌĆÖm finally in a safe place.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

That was until April 21, when a schizophrenic episode landed Dunkus, 48, in the emergency room at Mercy ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ in Creve Coeur. Once inside, she was taken to the emergency departmentŌĆÖs behavioral health unit for patients in a mental health crisis.

The unit is locked and separated from the rest of the emergency department. Little to no medical care is provided there, as patients wait, often for several hours, for an open bed in a psychiatric facility.

People are also reading…

At 7 a.m. the next day, Dunkus was found dead. An autopsy released June 12 revealed she died of complications related to long-term alcohol abuse. Her heart had failed.

Hospital workers directly involved with the care of patients in MercyŌĆÖs emergency behavioral health units say how Dunkus was treated exemplifies the poor conditions inside these units.

ŌĆ£It was not a matter of if this would happen. It was a matter of when,ŌĆØ said one worker.

The worker was one of four, including a nurse, who spoke on background to the Post-Dispatch, citing concerns about losing their jobs if they were named.

DunkusŌĆÖ family members say they have been given few answers from the hospital. Her medical records, copies of which her family provided to the Post-Dispatch, indicate numerous medical concerns, leaving them with more questions.

The records show Dunkus had dangerously low potassium ŌĆö an electrolyte that can affect the heartŌĆÖs electrical signals. An electrocardiogram (EKG) showed she had a concerning heart rhythm. Her blood pressure was high.

Benns said she also told doctors about her auntŌĆÖs history of alcohol abuse and how she had been complaining of chest pains.

Yet Dunkus was kept in the behavioral health unit with no heart monitoring, her records show. The only treatment she received was intravenous fluid containing potassium and magnesium. No or were used that could help regulate her heart.

ŌĆ£That wasnŌĆÖt the appropriate place for her to be,ŌĆØ said her sister Cheryl Ketter, 56, of Ferguson. ŌĆ£You canŌĆÖt just shove them into a corner somewhere and think that they are OK.ŌĆØ

The autopsy report notes that Dunkus was last seen alive at 11 p.m. ŌĆö eight hours before her dead body was discovered. From a central nursesŌĆÖ station, she was supposedly observed every 15 minutes via a video camera.

ŌĆ£All they did was just leave her in a room,ŌĆØ said her niece Rose Taylor, 25, of Mehlville.

Mercy officials say federal privacy laws prevent them from speaking about DunkusŌĆÖ death. In response to allegations about the quality of care provided by its emergency departments, hospital officials only released a general statement.

Officials insisted that all patients coming into a Mercy emergency department are appropriately screened to rule out emergency medical conditions and to determine if any tests or procedures are needed.

Patients are safe, they say, despite higher numbers they are having to care with behavioral health issues.

ŌĆ£Patients are monitored by nursing and other personnel throughout the ED visit to ensure their safety,ŌĆØ the statement read. ŌĆ£Increasingly, due to lack of access to mental health resources across the U.S., high-volume emergency departments such as Mercy have become a regular source of care for patients who are often in crisis situations.ŌĆØ

A difficult life

It was important to Dunkus to be at the births of every one of her 11 nieces and nephews. She babysat any time she could and hosted sleepovers.

ŌĆ£She was always that aunt that was there for a lot of us,ŌĆØ Benns said.

Kathleen ŌĆ£KatŌĆØ Dunkus

Dunkus was one of five siblings who grew up in the ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ area. As children, they ended up in foster care after their mother left and their father couldnŌĆÖt take care of them on his own, though he remained close with them.

DunkusŌĆÖ medical record shows her father also had , a serious mental illness that typically manifests in early adulthood and can cause hallucinations, delusions and extremely disordered thinking.

The five children were split up in foster care. Dunkus stayed with BennsŌĆÖ and TaylorŌĆÖs mother as well as their uncle. Life was difficult, Taylor said, ŌĆ£but they had each other.ŌĆØ

Their mom learned about her sisterŌĆÖs schizophrenia and helped keep the symptoms at bay. Benns and Taylor said they rarely saw their aunt experience delusions.

Dunkus earned a degree in human resource management, Benns said. She worked various customer service jobs, where she enjoyed helping people. She loved photography. She was proud of her Native American heritage on her motherŌĆÖs side and was a registered member of the .

Kathleen ŌĆ£KatŌĆØ Dunkus. Self-portrait taken in 2000 for a photography class. Dunkus, whose mother was Native American, was a registered member of the Oglala Lakota Nation.

But Dunkus also struggled with alcoholism, which with schizophrenia as a way to cope with the symptoms. It contributed to ending her 15-year marriage around 2016 and strained family relationships.

In 2010, DunkusŌĆÖ sister ŌĆö Benns and TaylorŌĆÖs mother ŌĆö died. That was followed by the death of her brother in 2018 and father in 2020.

ŌĆ£The deaths really took a toll on her,ŌĆØ Benns said. ŌĆ£She was trying to find her way back to more stability.ŌĆØ

Two years ago, Benns agreed to let Dunkus move in with her after she completed an alcohol treatment program. Dunkus came out healthy and hopeful, Benns said.

Benns and Taylor said they had watched their mother gradually get sicker as she was in and out of the hospital. It was different with their aunt.

ŌĆ£Looking back on my mom, you could see it coming,ŌĆØ Taylor said. ŌĆ£But with Kat, she was doing so much better.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśEight hours?ŌĆÖ

Two days before ending up in the emergency room, Dunkus began feeling paranoid, Benns said. The next day, she was hearing voices. Dunkus thought people were recording her. She was scared someone was coming to take her to prison. She accused Benns and her boyfriend of drugging her.

Benns said Dunkus admitted she had gone to a bar and was drinking again. Benns scheduled a doctor appointment for the following day.

The morning of the appointment, however, Dunkus left the apartment and ended up nearby at the Jewish Community Center, where an employee called police at 10:46 a.m., according to the police call log. Officers arrived a minute later to find Dunkus sitting in an office.

Police called Benns. The officer had called for an ambulance, which Benns followed to the hospital.

No police report was written, but Benns said part of the reason why police called for an ambulance was because her aunt said she had chest pain. DunkusŌĆÖ medical records show she arrived at Mercy ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ at 11:44 a.m. for ŌĆ£psychological evaluation.ŌĆØ

Kathleen ŌĆ£KatŌĆØ Dunkus with her two dogs Ava and Luciano in 2010. Courtesy photograph.

Benns said Dunkus was taken straight to the locked behavioral health unit within the emergency department.

Benns found her aunt getting her blood drawn and in what her nurse called a ŌĆö she was making tense, unusual movements, such as holding up her leg or her mouth open.

Benns said she talked to a doctor about her auntŌĆÖs chest pains. The doctor told her he would order an EKG of her heart and a CT scan of her organs.

DunkusŌĆÖ bloodwork revealed she had no alcohol or drugs in her system, according to the medical records, but her potassium level ŌĆö 2.7 ŌĆö placing her at higher risk of cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heart rhythm). Normal is 3.5 to 5.2. Anything lower than 3 is considered ŌĆ£severe.ŌĆØ

Dunkus refused to take pills or eat, so she was given an intravenous bag of fluids to raise the level, which requires continuous monitoring, , to ensure safety.

Benns and Taylor stayed with her for several hours. The EKG machine was brought into the room, they said. To go to her CT scan, Dunkus had to be lifted into a wheelchair. She was quiet.

ŌĆ£She was slightly responsive, or she wouldnŌĆÖt talk,ŌĆØ Taylor said.

Benns and Taylor said the only concern staff shared with them was her potassium level was low, and the goal was to raise the level so she could be admitted to an in-patient psychiatric facility.

Dunkus eventually wanted her nieces to leave, thinking they were trying to hurt her, they said. They didnŌĆÖt want to scare her, so around 7 p.m., the two left the hospital.

ŌĆ£I love you, and I hope you know we just want you to be safe and happy,ŌĆØ Taylor said she told her.

Benns, the main contact, was expecting to get updates throughout the night. Instead, Taylor got a got a call from a chaplain at 7 a.m. the next morning saying her aunt had died.

At the hospital, Taylor said a doctor and a nurse told her that her aunt was last checked on at 11 p.m.

ŌĆ£In my head, IŌĆÖm like, ŌĆśEight hours? Is that normal?ŌĆÖŌĆØ she recalled. ŌĆ£That is the only thing that stuck in my head, them telling me eight hours. They couldnŌĆÖt even tell me when she died.ŌĆØ

Complications

The hospital reported the death to the ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ County Medical ExaminerŌĆÖs office, in cases where the cause of death cannot be established. The office decided an autopsy was needed.

The examination concluded that the cause of death was complications from chronic alcohol abuse. The years of drinking had caused the .

When that happens, explained ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ County Assistant Medical Examiner Dr. Joshua Akers, the electrical impulses that travel through the heart ŌĆ£kind of get lostŌĆØ or travel slower.

ŌĆ£That can create a cardiac arrhythmia, and a serious arrhythmia can be fatal,ŌĆØ Akers said. The body is starved of blood and oxygen.

Death can occur in less than five minutes, he said.

One of the first signs of a severe arrhythmia would be losing consciousness, Akers said. If a person was sleeping, there might not be any signs.

After DunkusŌĆÖ lifeless body was discovered, CPR was administered along with two doses of epinephrine, records show. No heart activity was ever detected. She was pronounced dead at 7:07 a.m.

A doctor called to the bedside wrote ŌĆ£no recent vital signs available.ŌĆØ The doctor also described the body as ŌĆ£gray, cold to touch, had swelling on her back,ŌĆØ medical records show.

Akers said such descriptions can be subjective and thereŌĆÖs no way of knowing the time of death.

The workers say Dunkus should not have been kept in the behavioral health unit.

After her arrival, DunkusŌĆÖ blood pressure was 140/100 and heart rate was 110 beats per minute ŌĆö both high. Lab results came quickly, revealing the dangerously low potassium.

An EKG was completed within about two hours. The test showed a QTc interval ŌĆö the time it takes for the heart to contract and recover ŌĆö of 492. The interval is considered prolonged if greater than 460 in women, , and 500 predicts an ŌĆ£increased risk of life-threatening cardiac events.ŌĆØ

DunkusŌĆÖ long-term and recent alcohol use were noted in the medical records, and the CT scan results showed liver disease consistent with chronic alcohol use.

No observations were noted after 2:18 p.m., when Dunkus was marked as ŌĆ£stable.ŌĆØ Her last vital signs were taken at 1:04 p.m. Her blood pressure was still 142/92.

DunkusŌĆÖ blood was analyzed again, but the sample was damaged, possibly skewing the results that were released from the lab around 10:30 p.m., the records show.

Benns said after calling the hospital to try and learn more about how her aunt died, she was eventually told that Dunkus was watched via a video monitor and because she appeared to be sleeping, no one physically checked her because they didnŌĆÖt want to wake her.

A travel emergency room nurse who has worked in hospital systems in the ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ area says when she sees patients with a history of alcohol abuse in the behavioral unit, she is adamant they be moved to a medical bed because of how quickly they can deteriorate.

ŌĆ£If you have a patient who is an alcoholic, I absolutely will not take them on the behavioral health side. I will stomp my feet, throw a fit. No way,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£They turn too quickly, they do.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśJust touch themŌĆÖ

A room in the behavioral health unit of the Mercy ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ emergency department. Kathleen ŌĆ£KatŌĆØ Dunkus, 48, died of heart failure in April 2023 at Mercy ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ after she was put into a locked unit for psychiatric patients.

The Mercy workers who spoke to the Post-Dispatch about DunkusŌĆÖ death described the behavioral health units at both Mercy ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ and its sister hospital Mercy South.

At Mercy ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ, workers say, the unit includes nine patient rooms. Some basic medical equipment is kept behind locked doors in rooms, as well as a toilet. Patients can receive intravenous fluids. The central nursesŌĆÖ station sits behind a high counter.

Mercy South includes 10 rooms, four of which are in an overflow wing. The patients share a bathroom in the hallway. The nursesŌĆÖ station sits in a closed room with windows. No medical equipment is kept in the rooms, and family members are not allowed.

Patients in the units wear scrubs. Beds are bolted to the floor. Nothing can be in the rooms that can be used to hurt themselves or others. Doors to patient rooms must remain unlocked.

The units are staffed with a nurse, one patient care technician (two if patients are in the overflow wing) and a security guard.

Patients coming into the emergency room are supposed to be medically screened first and have blood drawn to check for abnormalities and drugs in their system before being sent to the units, the workers say.

One of six patient rooms in the behavioral health unit at Mercy South. The unit has an overflow area with four more patient rooms. The rooms have no medical equipment. The patients use a bathroom in a shared hallway. A nurse, patient care technician and security guard can sit in a closed room with windows, where they watch patient rooms on a video monitor. No family members are allowed in the unit at Mercy South.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve had them come straight from EMS, straight back here, and IŌĆÖm like ŌĆśLook, nuh uh, this patient needs to go over there, medically should be over there,ŌĆÖ and they wonŌĆÖt take them back ŌĆ”,ŌĆØ said the nurse. ŌĆ£But we have open rooms ŌĆö thatŌĆÖs how itŌĆÖs looked at. The behavioral has open rooms, use them. And IŌĆÖm like, ŌĆśBut I canŌĆÖt monitor them.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

Patients in the behavioral units should be able to walk, speak, use the bathroom ŌĆ£and have no medical needs,ŌĆØ she said, ŌĆ£meaning that for the most part, other than their mental health, they are healthy.ŌĆØ

But patients are sometimes sent there who are incontinent or in wheelchairs, the workers say. Some are not in mental crisis but emotional from grieving a death or an injury. Staff use the units as a way to reduce wait times, they say.

ŌĆ£There are times when a patient is highly agitated and being on a locked unit is the safest path for sure, and they need to get them over there quickly. We all understand that. But that is not how the unit is used,ŌĆØ one worker said.

That makes it harder for the one nurse staffing the unit to keep a watchful eye on all the patients, the nurse said. ŌĆ£I canŌĆÖt chart, I canŌĆÖt look at orders, I canŌĆÖt get the meds, do all that, plus look at the monitors, make sure everybody is OK, make sure I order meals and get the meals up here to them. You are only one person, you can only do so much.ŌĆØ

Patients in mental crisis who also have medical needs, the workers say, are supposed to be cared for in a medical room with a sitter continually watching them and noting their condition every 15 minutes ŌĆö such as sleeping, calm or agitated.

Routine in-person checks should also happen in the behavioral health units, but instead patients are observed via a screen from the nursesŌĆÖ station or not at all, as workers say they have caught patient care technicians doing homework or searching the internet.

ŌĆ£How hard is it to get up every 15 minutes to do a safety check? It is their actual job, and they canŌĆÖt get up to check?ŌĆØ said one worker.

The nurse says patients should have their vital signs taken at least every two hours. Patients can refuse to have them taken, but staff should continue to try. And if a patient hasnŌĆÖt moved after an hour, she said, they need to be checked physically.

ŌĆ£I have to count a lot on the (patient care) techs,ŌĆØ she said, ŌĆ£and if they are like, ŌĆśOh, they are fine, they are sleeping,ŌĆÖ IŌĆÖll say, ŌĆśWhen was the last time you went in there? I need you to be in there and just try to wake them up, just touch them, see if they move, whatever.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

But, she said, she understands that dealing with patients in mental crisis can be extremely challenging, exhausting and dangerous. She and others have been attacked by patients.

Mercy officials, in their statement, encouraged workers to report concerns to MercyŌĆÖs internal safety event reporting system, used to address concerns related to patient care and workplace conditions:

ŌĆ£We rely on our co-workers, patients and visitors to be the eyes and ears to report events and give us the opportunity to address any issues and create a safer environment for all.ŌĆØ

Benns and Taylor said while at the hospital, staff never told them the results of their auntŌĆÖs EKG or CT scan. The severity of the low potassium was never explained. ŌĆ£We should have been given this information so that we could advocate for her care,ŌĆØ Taylor said.

They also donŌĆÖt understand why DunkusŌĆÖ chest pains were not noted in her medical record.

ŌĆ£Their best solution for how to care for a catatonic patient with concerning health issues was to leave her in a room for eight hours,ŌĆØ Taylor said. ŌĆ£It really hurts us to know this is how someone we loved was treated.ŌĆØ

_____