George Seper was a detective sergeant in homicide in the early ’80s when I was night police reporter. In those days, the police department had no “official spokesperson,” and no public affairs staffers. Reporters got their information from the officers who were handling the cases.

Homicide detectives had a special notoriety. Ben Thomas of the Evening Whirl — a weekly crime newspaper — gave them nicknames. Sometimes the nicknames were descriptive — “Dapper Dan” Nichols was a snazzy dresser, John “Hollywood” Roussin was as handsome as a leading man. Other times Ben took literary license. George “the Creeper” Seper didn’t really creep. He did just the opposite. He charged.

He carried a small cassette player to homicide scenes. As he and his two detectives got out of their unmarked car to take over the scene from the district detectives and patrolmen, George would light a cigar and turn on the cassette, which would blast out the traditional calvary bugle command, “Charge.”

People are also reading…

“Dee dee, dee dee, dee dee.”

Some of the folks in the crowd who gathered at these scenes would nod to one another. Seper’s Creepers were on the set.

Investigations were different back then. There was no ShotSpotter to alert police to gunfire, no license plate readers to follow a trail, no cellphones to check to see who the deceased had been chatting with, no social media sites to peruse, no closed-circuit videos on nearby businesses to study, no DNA to help identify culprits. There was just a body.

In the absence of scientific evidence, there were informants and unspoken understandings and get-out-of-jail cards and lots of guesswork. A detective sergeant had to be smart and patient. None of this “first 48 hours” stuff. Cases took time to develop. Detectives had to be able to talk to people and make educated guesses about who was telling the truth, and how much of the truth they were telling.

It was a dark and imperfect world. George thrived in it.

He was a former Marine. He served in combat in Korea. He made the famous landing at Inchon as a gunner on an amphibious tank. He spent some time with Australian commandos.

But the most central part of his identity was this — he fell in love in the fourth grade.

He was born in July of 1930 in the early days of the Great Depression. His father was from Hungary. His mother was born in ӣ����Ƶ to Hungarian immigrants. Hungarian culture did just fine in south ӣ����Ƶ. Parties, food, and polkas were common.

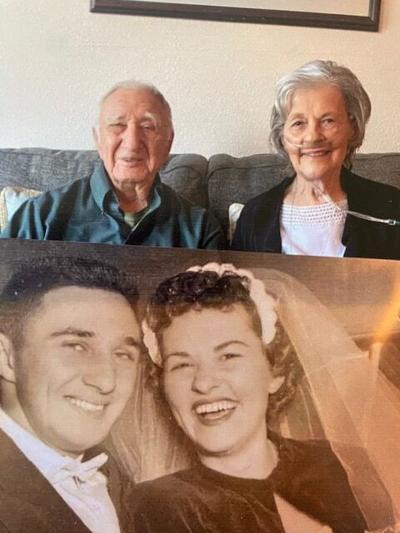

Young George was industrious. He hunted rabbits. He collected empty soda bottles. He worked as a delivery boy for a small grocery store. He attended elementary school at St. Bernard’s Church. It was there he met Dorothy Klein. He was in fourth grade. She was in third. George fell in love instantly. Dorothy was not so sure.

But George was persistent. Their first date was a month before she turned 16.

Still in love, George joined the Marine Corps after graduating from high school. On Dorothy’s 19th birthday, he gave her an engagement ring, and also the news that he would be leaving for Korea in a month.

He came home from the war in January 1952. He and Dorothy were married at St. Bernard’s Church. George got a job as an ambulance driver. On one of his calls, het met some Sisters of the Poor. He told them he wanted to be a cop. They said they’d pray for him. When he graduated from the Police Academy in October 1954, he took a bouquet of flowers to the Sisters.

He and Dorothy had three children — Tom, Janet and Judy. Judy remembers being with her dad at a drugstore when she was a young child. An older man approached and spoke to her dad in a language she didn’t understand, but her dad seemed to. After a brief conversation, the man left. Judy asked who he was. “I arrested him a long time ago and he went to prison.” “Is he mad at you?” she asked. “No. He didn’t want to go to prison, but he understands that I was just doing my job.”

Bad guys aren’t always bad people, Judy thought. Life was more ambiguous than she had imagined.

George appreciated firearms. He did ballistic research in his basement. He fired different weapons into blocks of clay. The kids knew not to make phone calls when their father was in the basement because it was unnerving to the person on the other end of the line to hear gunshots.

George retired from the police department in 1985. He charged into retirement. He hosted lunches at Pietro’s on Watson Road. Mostly old chums from Homicide, but other friends, too. Separate checks always, but George was the leader.

“The Seper table,” I’d say to the waitress when I walked in. “George is holding court in the back today,” she’d say.

When he was 75, he went bear hunting in Alaska. In his early 80s, he went boar hunting in Texas. A boar charged him. Big mistake for the boar.

One day, maybe 15 years ago, George had some exciting news at lunch. He pulled up his sleeve. He had a brand-new Marine Corps tattoo.

“You get one of those before you’re 20, or you don’t get one,” I said.

“The guys who get them when they’re 20, they’ll be faded when they die. Mine will be vivid,” he said.

Eventually, he and Dorothy moved into a senior living facility on Telegraph Road. Some residents decorate their doors with photos. George put yellow crime tape all over his and Dorothy’s door. It was easy to find.

Dorothy died in March 2022. Their son, Tom, died last year. George became more idiosyncratic than ever. He preferred eating out of his mess kit rather than the plates the facility provided.

George turned 95 earlier this month. His daughters planned a party on the Saturday after his birthday. A friend and I visited shortly before his birthday. George gave me a bottle of whiskey to give to a mutual friend.

“Any message with this?” I asked loudly. George could hardly hear, hardly see. “Jerry is going to wonder why you’re giving him a half bottle of whiskey.”

“Half bottle?” George said, puzzled. He looked at the bottle and then nodded his head in understanding. A joke. That’s a bad sign, I thought. Even at his advanced age, George is mentally agile.

“Why won’t the Lord take me?” George said. “I’m ready to go. I want to be with Dorothy.”

He died two days later, the day after his birthday.

Post-Dispatch photographers capture tens of thousands of images every year. See some of their best work that was either taken in June 2025 in this video. Edited by Jenna Jones.