ST. LOUIS ŌĆó He was preparing for the worst.

Every five to 10 years, Mark Stahlhut returns to the cityŌĆÖs College Hill neighborhood, a place he moved from more than a half century ago. Each time the decay seems to have accelerated.

ŌĆ£Whenever I had gone back, it was just emotionally devastating,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£Internally, I was always crying. There was no hope.

ŌĆ£Never any hope.ŌĆØ

He returned in the fall of 2013, expecting more of the same.

ŌĆ£I went with my partner. I wanted to show her where I grew up,ŌĆØ said Stahlhut, who lives in LaCrosse, Wis.

They pulled up to the old St. James United Church of Christ, where StahlhutŌĆÖs father was pastor for 13 years. It was the church where Stahlhut was baptized, his fatherŌĆÖs funeral held.

People are also reading…

In the black and white photo, the Stahlhut brothers Ralph (left), Don (center) and Mark, play on the front lawn of the St. James United Church of Christ campus in the College Hill neighborhood. The photo was taken a few years after their father, Herbert, became pastor of the church in 1947. While the brothers have visited individually, in 2014 the brothers returned to the church for the first time together. The Stahlhut brothers, Mark (left), Ralph (center) and Don, stand in front of their childhood home, the parsonage of the old St. James United Church of Christ in College Hill. Photos courtesy of the family

A man was working inside the gymnasium, one of four buildings making up the St. James campus. The basketball court was gleaming.

Something was happening here. Something that Stahlhut and his brothers didnŌĆÖt think they would see in their lifetime.

A church campus long neglected coming back to life. Idyllic childhood memories that had been obscured by blight, crime and neglect were returning.

Stahlhut, 68, could not wait to tell his brothers, Ralph and Don. For the first time since their father died in 1960, the three brothers were going to come back to College Hill together. To St. James. To learn more about the man who had purchased the church campus with the intention of helping transform a neighborhood.

And after a two-hour visit in September 2014, it was clear: The three men were going to become fundraisers for the fledgling nonprofit known as Urban Born, tapping into the old churchŌĆÖs congregation, now spread across the country.

The brothers decided on Holy Week to send out a letter promoting a church homecoming in May. ItŌĆÖs an opportunity to show new life at St. James, Don Stahlhut wrote.

ŌĆ£Easter fulfills the promise of new life. Urban Born fulfills that promise with new life at St. James Church.ŌĆØ

A fresh start

The man in the gym was Johnel Langerston, who purchased the St. James buildings, including the church, parsonage and Sunday School classrooms, in October 2012. He had just started a small after-school program focusing on education first and basketball second.

Langerston, 52, told Stahlhut and his partner, Janis Jolly, about how the neighborhood was overrun with drug dealers and violence and how black young people in this part of town are not getting the education they deserve. He told them about a string of murders and other gun violence that led to Police Chief Sam DotsonŌĆÖs move in early 2013 to saturate the neighborhood with 80 officers, vowing to snuff out crime.

This is a place white middle-class families had long abandoned, and now blacks were following. By 2010, the population of this neighborhood a few miles from downtown had fallen to 1,871 residents, a 37 percent drop over the course of a decade.

Langerston also talked about his past, describing it as ŌĆ£a unique and provocative rags-to-riches, destructive-to-preservative life story.ŌĆØ

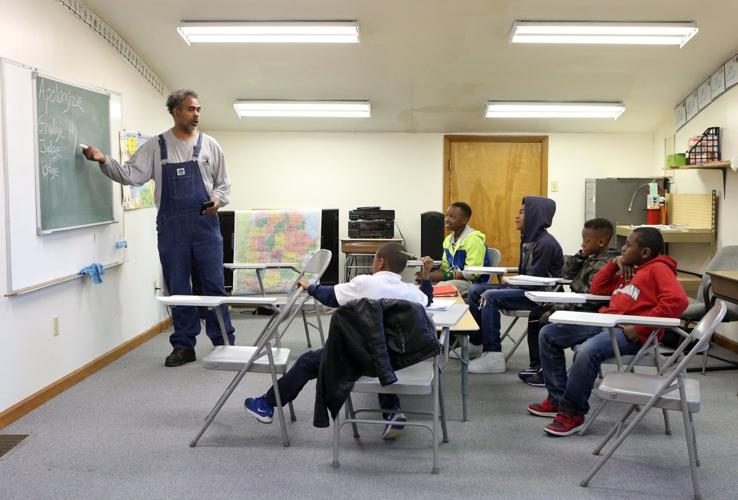

Ayinde Aldridge, 15, (left) and Dhavoni Allen, 10, were excited when they gave the right answer to their teacher, Johnel Langerston on Monday, March 21, 2016, at Urban Born in ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ. Urban Born is the former St. James Church on E. College Avenue. Langerston asked them to spell "disciplinary" which they spelled correctly. Photo by J.B. Forbes, jforbes@post-dispatch.com

He grew up in Oakland, Calif., and earned an associate degree in photography. When an injury sidelined him after being accepted on a track scholarship to California State University at Northridge, he returned to the streets, selling marijuana, then crack cocaine before serving a decade behind bars for drug dealing.

He began a marketing and production company in Los Angeles, which he still runs remotely from ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ, a place he says he arrived at by Googling ŌĆ£worst place to live.ŌĆØ ItŌĆÖs money from that business that he used to buy St. James and start the nonprofit.

He wanted to help young people find their way and not go in the direction that landed him in prison. He wanted a challenge and a fresh start.

He and his wife, LaTasha, live in the old Sunday School building and home-school their two young children. They run the nonprofit out of the gymnasium. Renovation of the parsonage and church will come later, as money and time permit.

Langerston is the center of his organization, serving as mentor, disciplinarian and main teacher. He relies on volunteers to help with math class and coach basketball. He is incensed that too many children are being promoted from grade to grade without knowing how to spell.

ŌĆ£We need to fix this disease,ŌĆØ he said. He points to the nonprofitŌĆÖs motto, written on a sign on the front doors: ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs Easier to Catch on Now, Than to Catch Up Later.ŌĆØ

Entrance to the after-school program is free but comes with a price. Children must prove they did their homework, which typically includes spelling words. Langerston uses teaching techniques from a A Beka Book, a home-schooling program.

ŌĆ£I was impressed with what he said he was going to do,ŌĆØ said Ralph Stahlhut, 74, of Maryland Heights. ŌĆ£But I was concerned he wasnŌĆÖt going to be able to do everything he wanted to do.ŌĆØ

Helping out

The Stahlhut brothers were determined to help out. Don, 71, who has a background in fundraising, took the lead. The brothers began putting together a list of former members of St. James and former residents of College Hill. They sent emails and letters and made phone calls.

They made contact with 52 people. From New York to California, Washington to Florida, 32 people sent checks, raising $5,150 last year. In a second round of solicitations this year, another $1,200 has been raised.

ŌĆ£It is a way for people to reconnect with the neighborhood, and reconnect with my dad. What he did was important to people,ŌĆØ Don Stahlhut said of his father, Herbert, who served as pastor from 1947 to 1960, when he died at age 43 from diabetes.

The brothers and their mother moved to south ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ, vacating the parsonage for the next pastor. By then, the neighborhood was changing. Families were moving out. Interstate 70 was a new addition to the neighborhood. The church eventually closed in 1979.

As the brothers would make individual visits to the neighborhoods over the years, it looked less and less like the place where they had church picnics, school parades and backyard ball games. Where children would climb the stone wall next door to watch the Pink Sisters pray at Mount Grace Convent or sled at nearby OŌĆÖFallon Park.

ŌĆ£I remember where my friends lived, and that was what was so hard. IŌĆÖd go by StevieŌĆÖs house, and wonder where he was at now. Oh, thereŌĆÖs PeggyŌĆÖs house. It looks like it is gutted,ŌĆØ Mark Stahlhut said.

My boyhood years ŌĆ£were just ripped out,ŌĆØ Don said. ŌĆ£My history of the neighborhood is no longer there.ŌĆØ

Jolly, MarkŌĆÖs companion, had heard him talk about the old neighborhood, and there was a bit of apprehension about visiting, she said.

ŌĆ£Mark was quite upset by not only the abandoned but the ripped-down buildings. It was going to be a sad day,ŌĆØ Jolly said. ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs what it looked like to me.ŌĆØ

But then they stopped at St. James and walked into the gym.

ŌĆ£It was amazing. He had redone the whole thing. It was a lot different than what I expected.ŌĆØ

Mark and Don followed their fatherŌĆÖs footsteps, becoming ordained ministers. Mark would end up working with at-risk children in LaCrosse, Don for an interfaith community organization in northern California.

Don saw living in Oakland as another connection to Langerston, who grew up there. Ralph stayed closest to home, living in west ėŻ╠ę╩ėŲĄ county. He retired from the printing business.

A sense of urgency

Langerston has seen do-gooders come and go most of his life, including at Urban Born, where the curious peek in, congratulate him on his efforts and move on. He figured the Stahlhuts would probably do the same.

ŌĆ£Johnel told us that the door has been darkened with good intentions. But when it comes to follow-up and support, he never sees them again,ŌĆØ Ralph said. ŌĆ£We didnŌĆÖt want that to be us.ŌĆØ

Langerston says he gets no grants, no city support. Aside from the Stahlhut money, the funding has been his own.

The number Urban Born serves is fairly small, about 25 children a week. Langerston hopes to expand with a summer program and open an elementary school in the fall.

Angela SampaŌĆÖs son, Mekhi, attends a Catholic school five minutes from Urban Born. She says her sonŌĆÖs spelling has improved significantly since he began working with Langerston, and she will move him to Urban Born when a new school opens there.

ŌĆ£Here, he is excited about learning. IŌĆÖve seen a change in him, especially with his confidence,ŌĆØ Sampa said. ŌĆ£This has made a big difference in his life.ŌĆØ

Langerston said some people found it hard to believe he would pick up his family and intentionally seek out a dangerous neighborhood. But there is a sense of urgency in his mission.

In 2012, he was diagnosed with sarcoidosis, a disease causing the immune system to overreact, which can compromise organ function. LangerstonŌĆÖs doctor said he could die within two years.

ŌĆ£I made it more than two years. And I feel pretty good. But now people may have a better understanding of why IŌĆÖm doing what IŌĆÖm doing.ŌĆØ