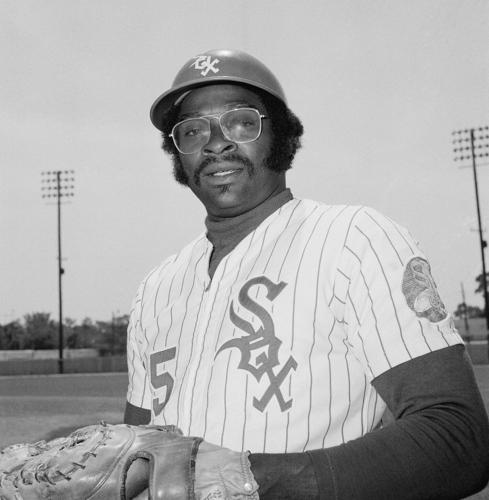

FILE - Chicago White Sox baseball player Dick Allen in 1973. (AP Photo/File)

At some point Sunday afternoon, Richard Allen Jr. will stand at the dais, the cadre of living Baseball Hall Famers sitting on the stage behind him, and deliver the acceptance speech for his late father, Dick, who will join those immortals with a plaque in Cooperstown, New York.

Thankfully.

Finally.

And sadly.

It took more than 40 years for the former Philadelphia Phillies star and one-time ӣ����Ƶ Cardinal to earn his place among the game's all-timers, for voters to recognize Allen's greatness and come to terms with all he had to endure and overcome.

Unfortunately, it seems way too fitting that Allen, who died of cancer in December 2020 at the age of 78, won't be there to experience it.

As William C. Kashatus wrote in his book "September Swoon: Richie Allen, the '64 Phillies and Racial Integration," Allen was "the wrong player in the wrong place at the wrong time."

People are also reading…

There's little doubt about that. Throughout his life, he never really got his due.

He has been misunderstood and/or misinterpreted. He didn't always get along with the mainstream media, which was almost exclusively white. Even the Phillies began by referring to him as Richie instead of his preferred name, Dick, and it stuck for years.

"It makes me sound like I'm 10 years old," he once said to George Kiseda of the Philadelphia Bulletin.

There's no denying that controversy seemed to follow Allen.

People remember his altercation with Frank Thomas in 1965, when Allen punched Thomas following a likely racially charged remark — reports over time vary — then Thomas responded by hitting Allen with a bat in the left shoulder.

People remember the messages he wrote with his spikes in the infield dirt at Connie Mack Stadium in 1969, when he wanted out of Philadelphia.

Or the time he injured his hand putting it through a headlight or ... the list goes on.

Overlooked — ignored? — have been the extenuating circumstances that led to Allen's behavior.

In 1963, just three years after graduating from Wampum High School in western Pennsylvania — "a community known for being relatively free of racial strife," according to Bruce Markusen in article on the Hall of Fame's website — and five after playing Columbia for the PIAA Class B boys basketball title, Allen found himself in the middle of a maelstrom not of his making.

He was the first Black man to play professionally in Little Rock, Arkansas, home of the Arkansas Travelers, which was in its first season as the Phillies' Triple-A affiliate.

On opening night, protesters outside the ballpark carried signs, a more tame one saying, "Don't Negro-ize baseball." Arkansas Gov. Orville Faubus threw out the first pitch, less than six years after he tried to block the integration of Little Rock's Central High School.

Following the game, Allen, in his 1989 autobiography "Crash," co-authored with Tim Whitaker, said he found a note on the windshield that began "Don't come back ..." and ended with a racial epithet.

He was the target of death threats that season. There were many places he couldn't go or eat in the city. He fought loneliness and the urge to quit.

FILE - Former Philadelphia Phillies player Dick Allen reacts after a ceremony unveiling his retired number prior to a baseball game between the Phillies and the Washington Nationals in Philadelphia, Thursday, Sept. 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Derik Hamilton, File)

In "Crash" Allen said: "There were two sets of rules in Little Rock, one for the Arkansas Travelers and one for Dick Allen ... That didn't go with me. From that day on, I decided if there was ever a double standard again, I would be the beneficiary, and not the other way around."

The next summer, Allen became the first Black star for the Phillies and emerged at a time of racial unrest in the city, which included riots near Connie Mack Stadium.

The Phillies' collapse in 1964, when they blew a 6.5-game lead with 12 to play, didn't help people's attitudes, either.

Eventually, Allen was the target of merciless booing.

He also earned a reputation for being a divisive force in the clubhouse and for not helping his teams win. Never mind that none other than the greatest player in Phillies history, Mike Schmidt, considered Allen, his teammate in 1975-76, one of his mentors and a guy who helped teach that young team how to win.

Yet through all the difficulties, Allen hit .292 with 351 home runs and a .912 OPS in his 15 major league seasons. He was the 1964 National League Rookie of the Year as a third baseman with the Phillies and the 1972 AL MVP as a first baseman with the Chicago White Sox.

Allen led the 1970 Cardinals in home runs (34), RBIs (101) and on-base plus slugging percentage (.937) in his one year here.

"He had a real intestinal fortitude to go along with that natural talent," his younger brother, Ron, said in a phone interview.

During a stretch of 11 seasons, 1964-74, Allen's .940 OPS and .554 slugging percentage trailed just Hank Aaron's .941 and .561. Allen's 165 OPS-plus was the highest among players with at least 4,000 plate appearances.

"He really, really had that enthusiasm," Ron Allen said. "He had more passion I wish that I had. If I had the passion that he had and anger; you just couldn't tell him that he couldn't do anything. He proved it to you. If I had that, ain't no telling where I'd have ended up. Hall of Fame. I might have been there myself."

Allen's journey to Cooperstown was a long one. In his 15 years on the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot, he never received more than 18.9% of the vote. Then twice he fell one vote short on Veterans Committee ballots — in Golden Era Committee voting in 2014 and 2021 — before finally making it this year through the Classic Era Committee.

When Richard Jr. makes his speech Sunday, it surely will be a bittersweet moment.

"I remember we were at a Hall of Fame banquet here in Lawrence County, and they were honoring my mother (Era)," Ron Allen said. "And my mother got up to speak, and she gave this speech on the greatest Hall of Fame that she had ever seen. And she said the Baseball Hall of Fame doesn't compare to my Hall of Fame. My Hall of Fame is in heaven.

"This is what we were always taught, because we had a Christian mother, and she taught us Christian values, and she instilled that in Dick.

"You know, the Hall of Fame is great — which we are really proud of, and like my nephews and nieces, they are over the moon over this thing — but being here to smell the roses, it takes a different plane with me, because it hurts my heart that he didn't get to see it, because he certainly deserved it.

"Even with the difficulties he had to go through, he withstood it, and I'm thankful for it, and I pray to God for it, and that's what I'll look at when I get there."

A look at the 2025 inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Ichiro Suzuki

Position: RF.

Teams: Seattle Mariners, New York Yankees, Miami Marlins.

How elected: Selected on 393 of 394 ballots (99.7%) by the Baseball Writers Association of American in his first year of eligibility, nearly becoming the first position player to be unanimous.

Notable: Finished his 19-year (2001-19) major league career batting .311 with 3,089 hits and 509 stolen bases despite not debuting until the age of 27. Spent the first nine seasons of his pro career in his native Japan, batting .353 with 1,278 more hits. ... American League MVP and Rookie of the Year in 2001. ... Was a 10-time All-Star, 10-time Gold Glove winner and won three Silver Slugger awards. ... Won two batting titles (.350 in 2001 and .372 in 2004). ... Set a major league single-season record with 262 hits in 2004.

CC Sabathia

Position: Left-handed starting pitcher.

Teams: Cleveland Indians, Milwaukee Brewers, New York Yankees.

How elected: Received 86.8% in balloting by the Baseball Writers Association of American in his first year of eligibility. Candidates need 75% to earn induction.

Notable: Went 251-161 with a 3.74 ERA in 561 games over 19 seasons (2001-19). Struck out 3,093, ranking 18th all-time, in 3,577.1 innings. ... AL Cy Young Award winner in 2007. ... Six-time All-Star. ... Won the World Series in 2009 with the Yankees; he was MVP of the AL Championship Series that season.

Billy Wagner

Position: Left-handed relief pitcher.

Teams: Houston Astros, Philadelphia Phillies, New York Mets, Boston Red Sox, Atlanta Braves.

How elected: Received 82.5% of votes in his 10th and final year on the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot.

Notable: Hard thrower was a seven-time All-Star who finished his career with 422 saves, ranking eighth all-time. ... Finished 47-40 with a 2.31 ERA and 1,196 strikeouts in 903 innings in 16-year career (1995-2010). ... Seven-time All-Star. ... Won the NL Rolaids Relief Man award in 1999.

Dave Parker

Position: OF, DH.

Teams: Pittsburgh Pirates, Cincinnati Reds, Oakland Athletics, Milwaukee Brewers, California Angels, Toronto Blue Jays.

How elected: Received 14 of 16 votes by the Hall's Classic Baseball Era Committee; 12 votes were needed for election.

Notable: Hit .290 with 339 homers and 1,493 RBIs in 19 seasons (1973-91), the first 11 as a feared slugger for Pittsburgh. ... NL MVP in 1978, when he hit .334 with 30 homers, 117 RBIs, 20 stolen bases and a .979 OPS. Also won one of his three Gold Gloves that season. ... Seven-time All-Star who was the game's MVP in 1979. ... Won two batting titles (.338 in 1977, 1978). ... Won World Series titles in 1979 with Pittsburgh and 1989 with Oakland. ... Died on June 28 at the age of 74 from complications of Parkinson's disease.

Dick Allen

Position: 3B, 1B, OF.

Teams: Philadelphia Phillies, ӣ����Ƶ Cardinals, Los Angeles Dodgers, Chicago White Sox, Oakland Athletics.

How elected: Received 13 of 16 votes by the Hall's Classic Baseball Era Committee; 12 votes were needed for election.

Notable: Hit .292 with 351 homers and 1,119 RBIs in 15 seasons (1963-77). ... Seven-time All-Star. ... Won the 1964 NL Rookie of the Year award. ... AL MVP in 1972. ... Died on Dec. 7, 2020, at the age of 78 due to cancer.