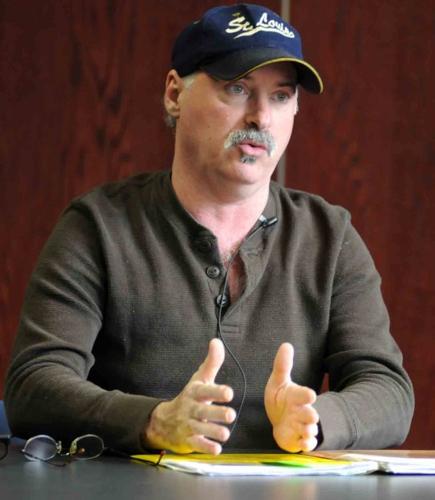

I'm sitting across from Larry Burgan as pulls out a folder teeming with assorted documents. Inside are various newspaper clips, photocopies, maps.

The assemblage represents the last few years of his life.

Burgan, 51, of Granite City, is here because he believes his job ruined his health. Burgan spent 14 years, from 1989 to 2003, as a press operator at a Venice magnesium foundry owned by Spectrulite Consortium.

Decades before Burgan's arrival, the sprawling factory, formerly under the ownership of Dow Chemical, was used by the U.S. government as part of its nuclear weapons program.

Now, on disability, Burgan's a self-styled crusader against the factory he believes poisoned him.

He spends his days ferreting out information, compiling data, meeting with politicians, lawyers, reporters. His work has paid dividends; in January, he was the subject of an extensive profile in the Riverfront Times. He has a pending worker's compensation claim that he expects will replenish his strained finances. He says his once-precarious health has improved.

People are also reading…

But he remains a man possessed.

Burgan and I traded at least half a dozen phone calls before we met. He was persistent. I was hesitant. This had nothing to do with the merits of his case - I just didn't have the time or resources to even scratch the surface of his story, which involved more than a dozen doctors and lawyers, by Burgan's count. Additionally, his story had already been thoroughly plumbed by the local press.

Burgan swatted away my concerns, and we met anyway.

Over the course of an hour, he told me his story.

ONLINE EXTRA: Listen to this story as read by the writer

Burgan worked at the magnesium foundry for 15 years, but never gave its nuclear research history much thought - until he was told a government clean-up crew would be coming to remove radioactive waste from the facility's roof.

Burgan's antennae shot up. He decided to play detective.

"I volunteered to work as a janitor so I could watch the clean up," he said.

To Burgan, it didn't look good.

"They were in moon suits," he said.

He work station was "boxed off in plastic." Burgan had images of radioactive dust dropping from above his workstation into his food and drinks.

Despite his misgivings, Burgan said he was assured that his health was not in danger.

A few months later he was at his doctor's office, complaining about respiratory problems. Shortly after that, he was complaining about terrible joint pain. Angry-looking red boils covered his skin. They remain there today.

He was diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis.

"Every joint in my body was seized up," Burgan said.

His wife had to walk him to the bathroom "like a 90-year-old man."

After a year he says he was bedridden.

As his physical condition deteriorated, his job at the factory followed suit. His union went on strike and Spectrulite Consortium declared bankruptcy shortly thereafter. Burgan was now unemployed and in poor health.

He then went into full Erin Brockovich-mode (a comparison he does not entirely shy away from).

Burgan began requesting state environmental records related to the factory, ultimately discovering that the spot directly above his workstation had elevated radiation readings.

He was convinced that exposure to uranium and thorium had sent his health into a nosedive.

Finding medical professionals willing to back that opinion up with testimony proved to be a problem.

Burgan also went through a series of "eight or nine" lawyers. While most were initially enthusiastic, they would ultimately tell him the case was missing "this or that."

"They didn't want to be the first and do all the work and research," Burgan explains.

He's also visited a series of physicians. But definitive proof of a causal relationship between his job and his failing health remained elusive.

Because he doesn't have a form of cancer that can be directly linked to radiation exposure, Burgan's attempts to qualify for a government fund that compensates exposed workers went nowhere.

Instead, he's pursued a worker's compensation claim against the insurer for the now bankrupt Spectrulite.

Though his plans for a civil suit stalled, Burgan is confident his worker's compensation claim will bear fruit.

He's expecting a settlement of about $800,000.

Despite the expected payout, Burgan continues to beaver away. He says he's willing to use some of the his expected cash to fund a radiological survey of homes in Venice. He fears residents near the factory have been sickened (he's not alone - a group of Venice residents recently aired these concerns during a meeting with a representative from U.S. Rep. Jerry Costello's office). There's talk of a class-action lawsuit.

Burgan made a compelling case. His life seems consumed by this task.

But after an hour with him, only one thing was truly clear: I have incredible sympathy for any jurors who might have to drop down this rabbit hole and render judgment.

Let us spend an hour with you

Know of interesting places where we should go or fascinating people we should meet for one hour? Send your ideas to Chris Campbell at ccampbell@yourjournal.com or call Chris at 344-0264, ext. 104.